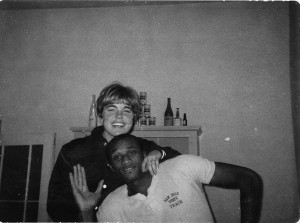

Here’s some black sports history for you from a white woman who lived deeply entrenched inside the black sports world for over thirty years. I had the female athlete’s view from the competitive level plus I had a unique view from above, being Wilt Chamberlain’s long-time companion until his death in 1999.

I was given my first lesson in “Negro” history in 1966 by Olympic gold medalist Tommie Smith and his roommate S.T. Saffold, the star player on our San Jose State basketball team. Together they pulled out their Encyclopedia of American Negro History and read to me of lynchings and other horrors to make sure this white college girl in California didn’t underestimate the wrath of white America’s reaction to my involvement with black people.

Sure enough, my all-white former high school friends were shocked, shook their heads, and some even withdrew from me totally. My father freaked and my mother turned silent, causing me to keep my life in the black sports world a secret second life separate from them.

All through my years at San Jose State, I trained alongside some of the world’s fastest sprinters. In fact, Track & Field News, called this unusual gathering “Speed City.” Bud Winter, a former Olympic coach, was our coach. While track coaches Vern Wolfe at USC and Jim Bush at UCLA wouldn’t allow women on the track while the men trained, Bud welcomed my eager desire to learn world-class sprint techniques. After the novelty wore off, the men accepted me and they gave me a head start to every sprint we did in practice, only to fly by me before the finish line. This was a time before there were any black faces on television, so learning black language on the track was thrilling.

Black athletes had trouble getting landlords to rent to them in San Jose in 1968, so I rented an apartment and turned the key over to two of my male teammates.

Watching Tommie push his black-gloved fist into the air on the victory stand at the 1968 Olympic Games was also thrilling. I watched that moment with the other sprinters from the track. As happy as we were about Tommie big gesture, that’s how unhappy all other white people were around me. “That was the wrong place,” or “that was disgusting,” were the comments I heard. These days it’s fashionable to admire Tommie for his courage, for providing a turning point in the history of black sports. But at that time, I had no other white friends to discuss it with. When Tommie took his stand, there was not a single black head coach in any sport in the college or professional ranks. All of that began changing slowly in the 1970s, slowly in the 1980s and 90s, then suddenly in this century.

The best wide receiver at San Jose State was named Calvin, who was black. Eric, who was his back up, was white. There were times that the coaches took Calvin out of the game and we had to watch Eric drop the ball. When I asked Calvin what that was about, he told me they could only put five black players on the field at a time. So if one went in, one had to come out. This was the first I heard of a quota system in football.

I met Wilt in Houston for a week-end and watched his Lakers play the Rockets in the Astrodome. I could have used a pair of binoculars – the tiny wooden court was so far away. I asked Wilt about a particular switch of players at one point in the game. He told me there always had to be two white players on the court. Ok, so there was a quota system in basketball, too.

My first coaching job was at Federal City College in Northwest Washington, D.C. I was the only white person there, student or instructor. I had thought it would be a lot like being in the sports world, but these were illiterate people in a two-year inner-city junior college. Drugs, violence, and absenteeism were rampant. Even the teachers who had come through the same school system didn’t show up for class very often! It was a shock, but I was determined to make it through the school year.

We had a pool and some space that was almost a gym, but we had no outdoor fields, so we were bussed over to the mall to play field hockey on courts right next to the reflecting pool and the George Washington Monument. When spring came, we were bussed over to the Georgetown University track. Whenever I started with a new group that was coed, I would bring along a football. We got to the track the first day and the guys didn’t want to listen to a white girl who wasn’t much older than them. I picked up the football, pointed to the biggest, most athletic-looking guy there and said, “You! Run a post pattern,” and pointed downfield. He frowned, pursed his lips, and made faces of disbelief with his friend. But he ran. I threw a perfect spiral 30 yards down the field right into his hands. From then on, I could coach.

In 1973, Tommie Smith and I were coaching together at Oberlin College, which proudly stated it had admitted the first two black male students in 1835. When I first got to town, I rented an apartment. Before I moved in, Tommie came with me to see my new place. The elderly white landlord took one look at Tommie walking beside me and took back my key. She said it was a mistake – she had forgotten that it was already rented. We realized that Oberlin may have made a progressive move in 1835, but it was still very racist 140 years later.

The summer of 1974, the NFL Players Association was on strike, and the Redskins were training on the Georgetown track, my home track when I was in D.C. I worked out with receivers Frank Grant, Roy Jefferson, defensive back Mike Bass, offensive guard George Starke, and quarterback Sonny Jurgenson.

In 1975, I was wrapping up the writing of my autobiography, A Running Start: An Athlete, A Woman. I stayed at a friend’s house in Georgetown. His family was on vacation, so he gave me the key. After an evening out dancing in Georgetown, I invited Frank and George back to the house. The next day my friend who was in San Diego called me to say that his parents had gotten complaints about black men going into their house and I was going to have to leave.

“When we’re Redskins, they treat us like folk heroes,” George said. “But we were just black men that night as they looked out their windows.”

The first-ever World Athletic Championships were happening in Helsinki, Finland in August, 1983. I was filing stories as a freelance sports journalist for National Public Radio. Wiltie met me there and as we sat in the stands, all the black faces except Wilt’s were on the track, and all the white faces were in the stands. I’m almost obsured sitting to Wilt’s left.

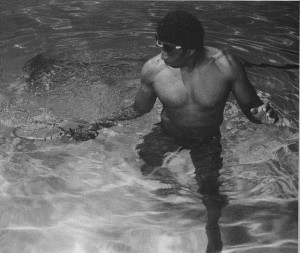

As the Los Angeles Olympic Games were unfolding, my writing mentor, Zan Knudson, suggested we write a book about the new water exercise program I had developed. She thought up the name of Waterpower Workout. We hired the black photographer I’d met when I was coaching at Los Angeles City College. We needed over a hundred photos for the book and decided to use my athlete friends. We asked Wilt Chamberlain, Olympic sprinter Evelyn Ashford, Olympic 800 meter runner Kim Gallagher, and NFL tight end Bernie Casey, among others.

We were both very proud of the fact that this was the first exercise book in America that used black models.

In 1986, I coached a young UCLA 400 meter runner in the pool while his injury healed. It amazed me that he didn’t know who Tommie Smith was, that he had never heard of the quota system for sports teams, but that he had heard of Bud Winter, our coach at San Jose State. He quizzed me on what it was like having Bud as my coach. Besides the coaching techniques that I shared with him, I found it really interesting that I was teaching this young black man his own black history. He simply didn’t know it.

A mudslide in Bormio, Italy would have gone unnoticed to me if friends in Lake Como hadn’t invited Wiltie and me to attend their fund-raiser, an Italian sports awards gala on New Year’s Eve, 1989. I had met Italy’s best 100M sprinter, but all the rest of the athletes were unknown to me. When the guest of honor, Wilt, took the stage, I watched how he raised one arm over head to acknowledge the uproar. He had the grace of a superstar long accustomed to the glare of the spotlight, while the others had blinked and acted shy.

There were no other black folks at the event, something that never fazed Wiltie. Since he had grown 7 feet tall at age 14, the white world had come calling and given him special exemption from most of racisms deprivations. He understood that and we talked about it on the flight home – but not until after he beat tenor Luciano Pavarotti at cards as they sat across the aisle from each other in first class.

Lynda Huey, M.S., founder of CompletePT and Huey’s Athletic Network, is a former athlete and coach whose own injuries led her into the water to find fitness and healing. She was educated at San Jose State University where she starred on the track and field team during its golden years. Lynda is the author of four books on water exercise and water rehabilitation.