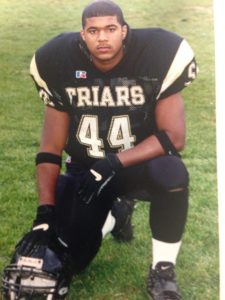

Frantz Lerebours was a linebacker at St. Anthony’s High School, a perennial sports power house football team on Long Island, New York. For three years, the team had been undefeated in the regular season only to lose the championship game to Monsignor Farrell from Staten Island, New York. Now, in his senior year, he was the starting outside linebacker. His team was nationally ranked on USA Today’s top fifty high school football teams in the country. Once again they were playing Monsignor Farrell for the championship game.

Frantz Lerebours, star linebacker at St. Andrews High School, Long Island, NY.

“Two minutes left in the game,” Lerebours remembered. “We were up by two. They were punting. The middle linebacker Ted and I came off the left side together. He was bigger than me, but I was faster. He blocked a defender and I dove with my hands out. The football hit my thumb, then it hit Ted in the back and bounced right in front of me. I grabbed it. It happened so fast. I thought my dream had come true. We were about to be #1 in New York State. Yes, I put us in a good position to win, but our offense turned the ball over, and the other team kicked a field goal and won the game by a point. I haven’t told that story in years, but it’s still right there.”

That’s Frantz Lerebours – the one who remembers the moment of brilliance that lit up his heart and still smiles with excitement as he tells the story. He’s long since gotten over the huge disappointment of losing that game.

“I was recruited to play for several Northeast liberal arts colleges, but I knew I wasn’t big enough to be a professional. I’ve always been reasonable and practical. I was 5’10”, 200 lbs. and strong. But I could size up the other guys. There’s no way I could compete with them. They would have knocked my head off,” he says laughing. “I knew I was interested in academics. I spent the summer prior to my senior year of high school at Columbia University doing a genetics and molecular biology summer course. That was my first exposure to advanced science with a lot of cool genetic mapping with fruit flies.

“I came from a family of medicine, so in high school I was thinking I would be a doctor. I thought about ophthalmology, which is what my father did. I didn’t like the microsurgery aspect and the small surgical field. Plus I didn’t like being in the dark all day.”

Frantz Lerebours went to medical school at Howard University in Washington, D.C. and loved it. At his mostly Irish middle school, St. Patrick’s, he and his sister were the only two African-American kids. So it was a great experience for him to be in a school where the majority of the students were black. Howard University’s mission statement says they are training physicians to serve the underserved and take care of the community. That felt good to the doctor-to-be.

“A lot of times, the medical students at Howard are nudged into primary care, but I was part of the second class of Nth Dimensions’ summer internship program, which has a goal to increase exposure with women and minorities into orthopedics. Nth Dimensions is partnered with Zimmer, a medical device company, and for thirteen years, they have been providing scholarships for two- month orthopedic internships. I spent a summer with orthopedic surgeons William Long, M.D. and Larry Dorr, M.D. at the Arthritis Institute at Centinela Hospital in Los Angeles.

“It was the first day. I had never scrubbed into surgery before. I didn’t even know how to scrub. I mimicked what Dr. Long did and focused on not contaminating the surgical field. It was an overwhelming experience. I enjoyed watching the concerted movements as instruments passed from the surgical tech to the surgeon like an efficient factory assembly line. My heart was racing with the excitement as I watched the surgeon reconstruct a knee. I loved the fact that we weren’t giving this patient a pill or a lab result. I loved the immediate gratification of seeing the deformity of the knee on the X-ray before surgery, hearing the plan of how we were going to correct the knee a certain number of degrees to realign it, then seeing the post-op X-ray to see that we did it. And since I was seeing patients with Dr. Long for eight weeks, I got to see the patients who had surgery the first week walking independently by the eighth week and they were so happy. I loved it! It was that moment I knew I wanted to be an orthopedic surgeon.

Orthopedic surgeon William Long, MD (left) pictured with Dr. Lerebours as he scrubs for the first time in his career.

“After med school at Howard, I went back to NYU for my residency. It’s one of the biggest residency programs in the country with twelve residents a year, and it is known as a military-style program. They have high expectations, so if you mess up, they’re not afraid to tell you, believe me. They taught me to dot my i’s and cross my t’s. I remember putting a cast on a patient with a broken ankle, but the next day they saw on X-ray that it was slightly out of alignment. I had to call the patient back and have him come in again so I could correct it. Now I appreciate how meticulous they made the residents be.”

During that residency, Dr. Ron Israelski, CEO and President of Orthopedic Relief Services International (ORSI), asked the residency director at NYU to go along with his medical team on the next trip to Haiti. ORSI’s main goal is to help build back the orthopedic services at the largest hospital in Haiti after it was destroyed in a devastating earthquake. Frantz was the only person of Haitian descent doing the NYU residency, so they looked to him first to go along.

“I speak the language; my family is from there. When they offered me this opportunity, I didn’t hesitate. I said, ‘Sign me up.’”

Dr. Lerebours’ parents were Haitian Refugees in the mid-1970s and his ophthalmologist father set up shop on Long Island, New York. His dad had seven siblings, three who are doctors, three who are engineers. One stayed in Haiti and all the others moved to Florida, New York, California, and Canada. Frantz was born and raised on Long Island. He was immersed in Haitian culture with his family and cousins.

“Over the years, I watched how the Haitian economy declined and the corruption got worse and worse and the country become more dangerous. My parents never went back. Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere with the worst history of natural disasters between earthquakes and hurricanes. When I visited, there were a lot of people displaced, living in tents. It was an eye-opening experience. My parents left Haiti on a whim back in the 1970s when things weren’t so bad yet. Sometimes I think about what my life would have been if they’d stayed there. That was an introspective experience to say the least.”

Yet Dr. Lerebours travels to Haiti several times a year with Orthopedic Relief Services International.

“We don’t just go down there and do surgeries and leave. We want them to be self-sustaining and establish their own orthopedic residency program. We’ve been bringing down books and equipment over the last few years. My goal is to establish arthroscopy there. They don’t have the equipment. They recently got a tower, which is what the cameras and surgical tools are hooked up to, but they don’t have the tubing. Even saline is scarce. It’s so valuable because of the diarrhea and the diseases, that even saline to flush into a joint, which seems like no big deal to us, could be a very big deal there and save someone’s life if they’re dehydrated from cholera.”

Dr. Lerebours in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, during one of his earlier medical missions to the capitol’s public hospital.

While Dr. Lerebours travels to Haiti frequently, he has also stayed focused on his career. After his five-year NYU residency came an orthopedic surgery fellowship at the Kerlan-Jobe clinic in Los Angeles. He wanted to learn from the illustrious sports medicine faculty there – doctors such as Neal ElAttrache, James Tibone, Ronald Kvitne, John Itamura, and Clarence Shields. And it turned out he learned almost as much from the other fellows who were training with him.

“A lot of us were from the East Coast. We became very close and did a lot of our research together. We had unlimited access to the cadaver lab, so we had the luxury of being able to do nearly any surgery we wanted right there on site. That was invaluable. It’s one thing to watch an associate do a surgery and it’s another to have the ability to do the surgery yourself on a cadaver with the actual instruments that you use in surgery and work through some of the problem-solving issues.

“I got a lot of experience treating the injuries of hockey, baseball, and basketball players while at Kerlan-Jobe. The injuries that come with football and basketball are often seen in the community, but most of the problems that come from baseball are overuse injuries from throwing. That means treating baseball players is entirely different than treating hockey players. With hockey players, you just patch them up and get them back out on the ice. But with baseball players, you have to shut them down, and you’ve got to watch their pitch count. There are so many different injuries in baseball, and it seems like all the players have pathology. The intricacies of taking care of throwing athletes lie in the realm of knowing which to fix and which ones to treat conservatively. That’s the art. Dr. ElAttrache has that down to a science. He understands that if you surgically repair a shoulder, throwers may no longer be able to reach into the full range of the late cocking phase and they may never play again. He’s watched baseball players for years and he has a sixth sense that lets him easily pick out the problem. I learned a lot in during my fellowship that I now apply to the shoulder patients I treat.”

Following his fellowship at Kerlan-Jobe, he joined Cedar Sinai Medical Group and began working with the illustrious orthopedic surgeon and well-known radio talk show host Robert Klapper, M.D. Dr. It seemed Klapper, who for 30 years worked as a solo practitioner, was searching for another doctor to join him.

“It was a Saturday morning. I woke up and looked at my phone and I had a text message and voicemail from Dr. Klapper,” he says smiling. “We’d never met or talked before he said, ‘Hi, Dr. Klapper. I got your CV from Dr. Gabriel (orthopedic surgeon also at Cedars-Sinai). Come down and meet me at my Manhattan Beach studio around 10 o’clock this morning.’ I got dressed, hopped in my car and went down there. It was a hot morning. I walked up to his studio and saw all these beautiful sculptures. He came out wearing blue scrubs and gave me a big hug. It was a very relaxed meeting. He reminded me of back home – a very well-spoken New Yorker with a big personality. Bibi Vabrey, Dr. Klapper’s office manager, came walking by and joined us for an interview. At the end, he looked at Bibi and said, ‘I think we have our guy.’ Within two weeks, I was spending time with him, shadowing him. I was learning how he takes care of patients and how everything works at Cedars.

Dr. Klapper’s Manhattan Beach studio.

So for the past two years, Dr. Lerebours has been building his practice. Now is the time he gets to see patients coming back to him from surgeries he did in his first year. He gets to observe their return to sport, such as a former patient who recently emailed him.

Hello Dr. Lerebours,

Last year, you performed a hip arthroscopy for a labral tear I had in my right hip and on my last office visit, I asked you if I would be able to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro in a year. Your response: only if I send pictures. Yesterday, I returned from Tanzania where I spent almost a month tutoring members of the Masai tribe, building schools on the island of Zanzibar, and on July 14th (exactly 1 year, 1 month, and 1 day after my surgery), I summited Mt. Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa, one of the seven summits, and the tallest freestanding mountain in the world. Thank you for fixing me up and I hope you enjoy a few of these photos from my climb 🙂 E.U.

Dr. Lerebours’ patient at base camp the night before summiting Mr. Kilimanjoro.

He continues to stay at the forefront of cutting-edge surgeries. He is one of the few surgeons at Cedars-Sinai to perform a total hip replacement using the new Direct Superior Approach. The Direct Superior is a muscle sparing approach which does not enter the large tendinous structure referred to as the iliotibial band (IT band). This can mean patients have less pain those first two weeks when walking around. And he closes the joint capsule, which helps retain the proprioception fibers that provide the body’s sense of position. This is an advancement from the Posterior Approach, which has been the primary method for decades.

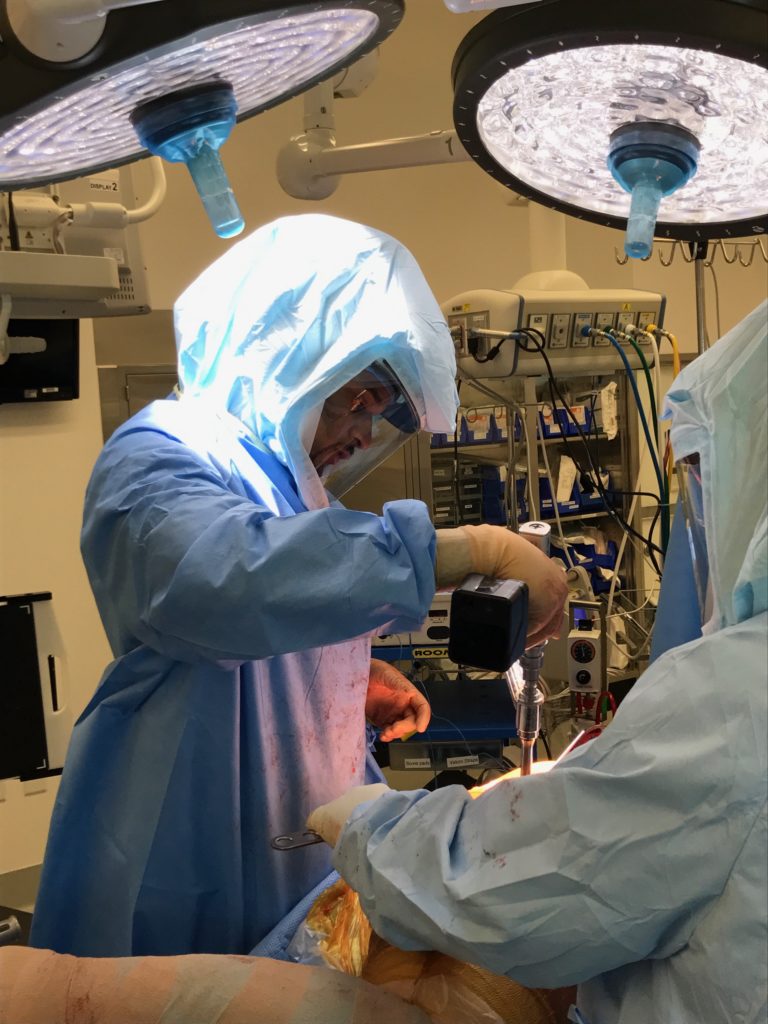

Dr. Lerebours performing Total Hip Arthroplasty using the Direct Superior Approach.

“The Posterior Approach is the work horse. It’s what 99% of orthopedic surgeons learn when they are training. If you’re going to do anything complex, that’s the way to do it. But it cuts the IT band, which means it can be a little more painful for the patient.”

In 2016, Dr. Lerebours traveled to Japan to learn an innovative shoulder surgery from orthopedic surgeon Teruhisu Mihata, M.D., PhD. The Superior Capsular Reconstruction surgery can be used instead of a Reverse Shoulder surgery, which was not approved in Japan. So Dr. Mihata created this surgery of necessity.

“It’s a rare surgery. Not that many people are walking around with a massively torn rotator cuff and inability to raise their arm. I saw Dr. Mihata do this surgery with great success and I’m prepared to do it here in L.A. so people won’t have to fly to Japan for it.”

Dr. Lerebours observing orthopedic surgeon Teruhisu Mihata, M.D., PhD, perform the latest cutting-edge shoulder surgery, Superior Capsular Reconstruction, 2016.

Last summer Dr. Lerebours had the fine pleasure of being the preceptor for medical student, Adam Wright, through Nth Dimension, the group that moved him toward being an orthopedic surgeon in the first place. “It was full circle. Now it was my turn to get to give back,” he said.

Dr. Frantz Lerebours in his office, instructing medical student Adam Wright from the University of Illinois, Chicago. Over a decade ago, Dr. Lerebours was in his shoes as an aspiring orthopedic surgeon.

When orthopedic surgeon Dr. Robert Klapper, who has more than twenty-five years of experience, leaves the office for a week, it’s up to Dr. Lerebours to cover for him as well as handle his own patients. Perhaps the word protégé is too simplistic to describe their relationship. When Dr. Klapper was asked how he chose Frantz Lerebours and what makes it work, he replied succinctly: “His humility/empathy/humanity and judgment.”

Meanwhile, Frantz Lerebours enjoys the Southern California outdoor culture. He loves rowing, paddle boarding, snowboarding, and hiking. He loves all things aquatic – in fact, he swims many mornings before starting his day. His career is starting to shape up nicely.

“I’m doing just about everything right now like most new orthopedic surgeons. I repair a lot of trauma fractures, then I’ll do a rotator cuff, then I’ll do a hip replacement. Still, I’m an athlete at heart and know I’ll end up focusing on sports medicine.

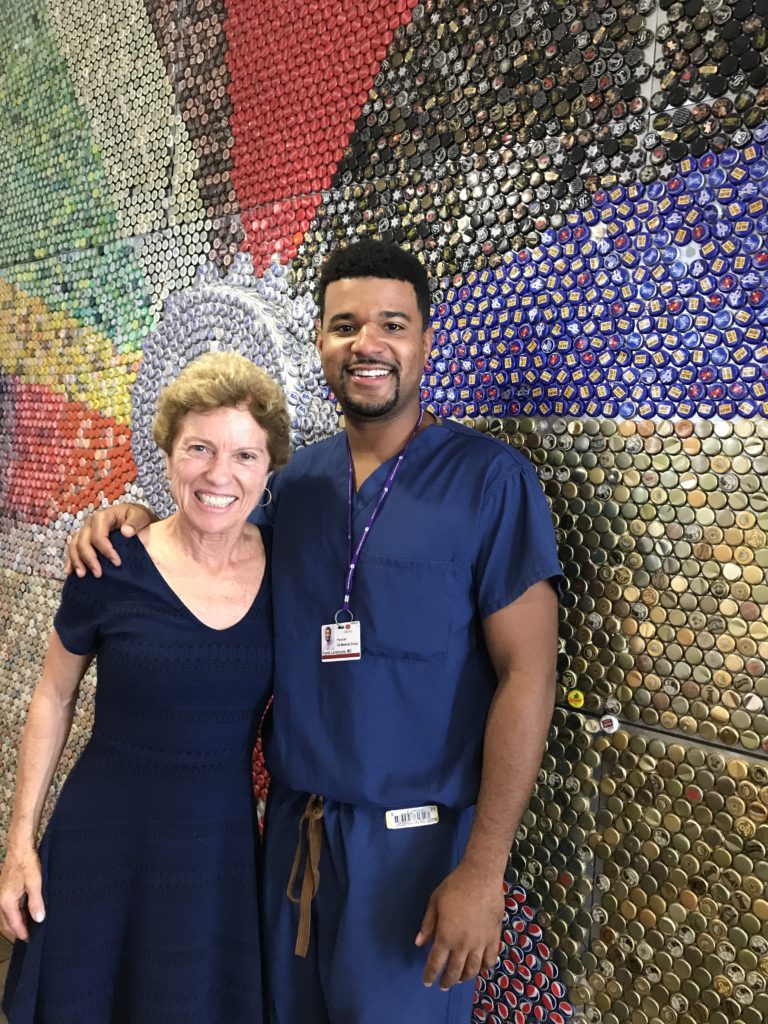

Lynda Huey and Dr Frantz Lerebours

Water Rehab Specialist, Lynda Huey, MS, earned a bachelors and masters degree from San Jose State University where she also starred on the track and field team. Her own athletic injuries led her into the water where she learned to cross train and speed the healing of injuries. She has written six books on aquatic exercise and rehabilitation, books that are considered the foundation of aquatic therapy world-wide. Lynda is President of CompletePT Pool & Land Physical Therapy in Los Angeles.